In the Midst of Rising Unknowns, Focus on What We Do Know

As someone famous (or infamous depending on your leanings) once said, “there are known knowns….there are known unknowns…but there are also unknown unknowns.”

We’ve got a whole lot of the second two going around these days and that is not good for growth. Life and investing requires dealing with uncertainty to be sure, but holy cow these days investors and businesses are facing a whole other level of who-the-hell-knows and that is a headwind to growth.

- The bumbling battle over Brexit

- China’s earnings recession

- Slowing in Europe

- Yield curve inversions

- Record levels of frustration with

Capital Hill - The Cost of Corporate Uncertainty

- The battle over the GDP pie

- Beware Reversion to the Mean

Brexit

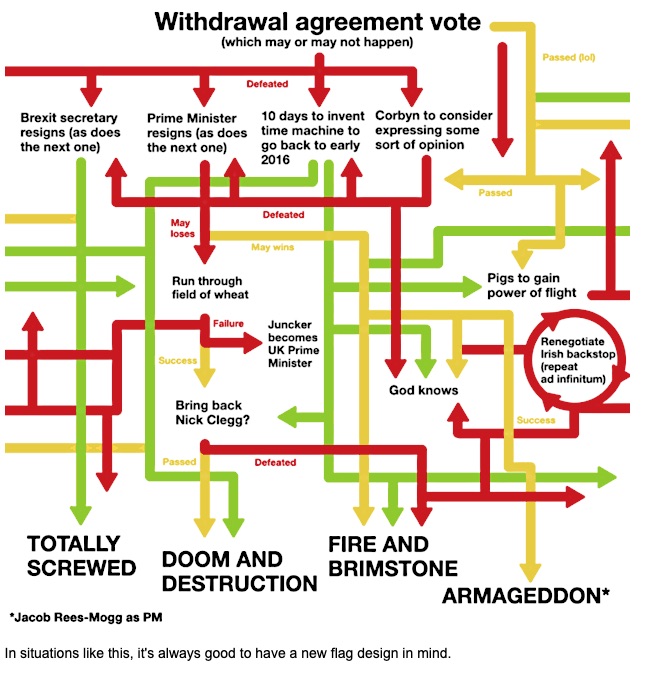

The United Kingdom, in or out? The mess that has become of Brexit is wholly unprecedented in modern history. As of March 29th, the day the UK was set to leave the EU, Brexit has never been more uncertain nor has the leadership of the UK in the coming months. This graphic pretty much sums it up.

Many Brits are unhappy with the state of their nation’s economy and are blaming those folks over in Brussels, as are many others in the western world – part of our Middle Class Squeeze investment theme.

China

Its economy is slowing, but just how bad it is and just how dire the debt situation in the nation is difficult to divine given the intentional opacity of the nation’s leadership. The ongoing trade negotiations with America run as hot and cold as Katy Perry depending on the day and when you last checked your Twitter feed.

Most recently China’s industrial profits fell 14% year-over-year in the January and February meaning we are witnessing an earnings recession in the world’s

Europe

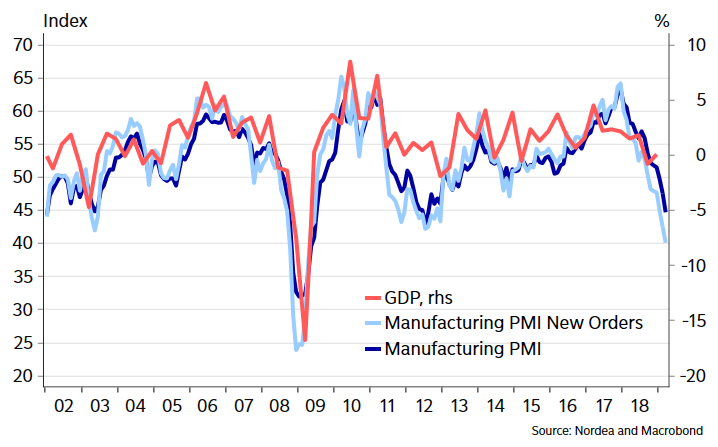

Last week the markets ended in the red, driven in part by weaker than expected German manufacturing PMI from Markit with both output and new orders falling significantly – new orders were the weakest in February since the Financial Crisis.

It wasn’t just the Germans though as the French Markit Composite Index (Manufacturing and Services) dropped into contraction territory as well in February, coming in at 48.7 versus expectations for 50.7, (anything below 50 is in contraction). The French PMI output index is also in contraction territory.

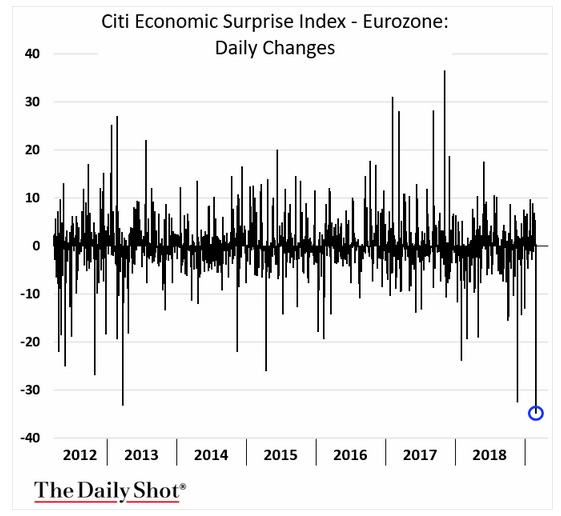

This led to the largest one-day decline in the Citi Eurozone Economic Surprise Index in years, (hat tip TheDailyShot).

Yield Curve Inversion

This pushed the yield on the German 10-year Bund into negative territory for the first time since 2016 while in the US Treasury market, the 10-year to 3-month and 10-year to 1-year spreads went negative – an inverted yield curve which has been a fairly reliable predictor of US recessions. The 10-year 3-month inverted for the first time in 3,030 days – that is the longest period going back over 50 years. The Australian yield curve has also inverted at the short end.

No Love for Capital Hill

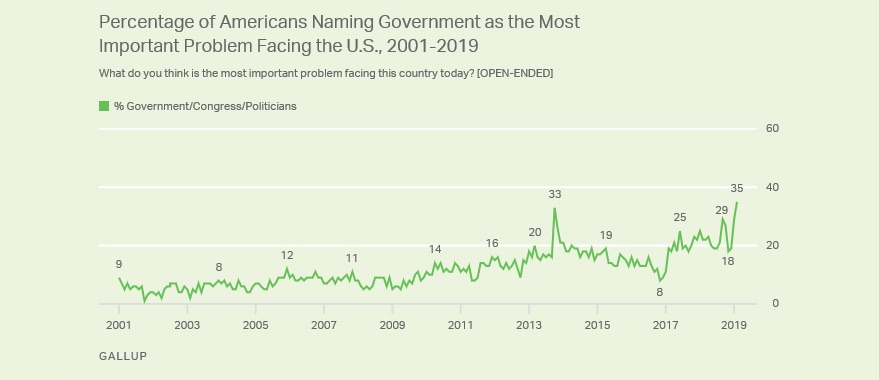

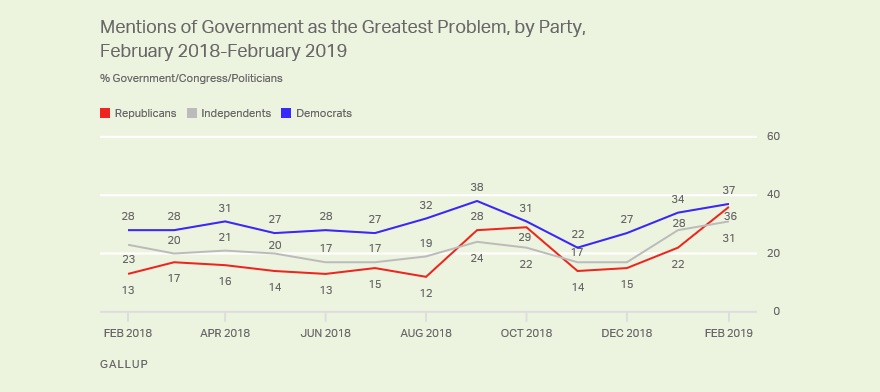

Americans’ view of their government is the worst on record – another manifestation of our Middle-Class Squeeze Investment theme. Gallup has been asking Americans what they felt was the most important problem facing the country since 1939 and has regularly compiled mentions of the government since 1964. Prior to 2001, the highest percentage mentioning government was 26% during the Watergate scandal. The current measure of 35% is the highest on record.

Few issues have every reached this level of importance to the American public: in October of 2001 46% mentioned terrorism; in February of 2007 38% mentioned the situation in Iraq, in November 2008 58% mentioned the economy and in September 2011 39% mentioned unemployment/jobs.

While America appears to be more and more polarized politically, the one thing that many agree upon, regardless of political leanings – government is the greatest problem.

It isn’t just the US that is having a tiff with its leaders. Last weekend over 1 million (yes, you read that right) people protested in London calling for a new Brexit referendum – likely the biggest demonstration in the UK’s history and then there are all the firey protests in France.

The Cost of Corporate Uncertainty

When companies face elevated levels of uncertainty, they scale back and defer growth plans and may choose to shore up the balance sheet and reduce overhead rather than invest in opportunities for growth. So how are companies feeling?

A recent Duke CFO Global Business Outlook Survey found that nearly have of the CFOs in the US believe that the nation will be in a recession by the end of this year and 82% believe a recession will have begun before the end of 2020.

It isn’t just in the US as CFOs across the world believe their country will be in a recession by the end of this year – 86% in Canada, 67% in Europe, 54% in Asia and 42% in Latin America.

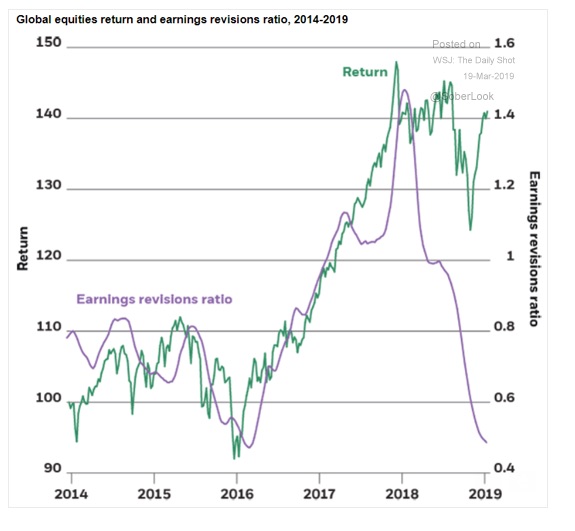

All that uncertainty is hitting the bottom line. Global earnings revision ratio has plunged while returns have managed to hold up so far.

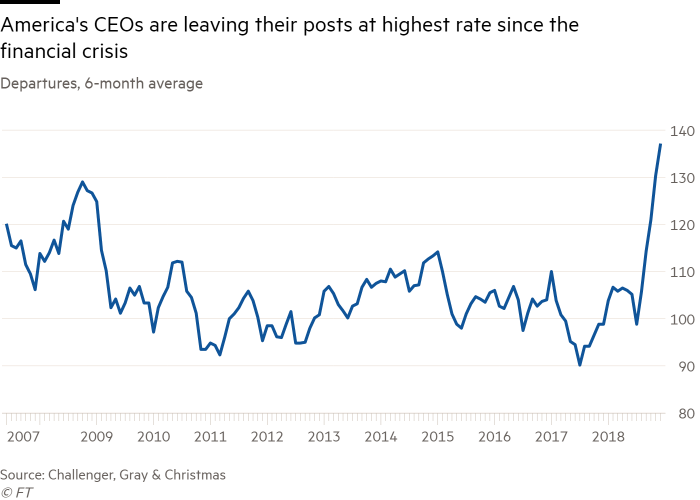

It isn’t just the CFO that is getting nervous as CEOs are quiting at the highest rates since the financial crisis – getting out at the top?

The GDP Pie

To sum it up, lots of unknowns of both the known and unknown variety and folks are seriously displeased with their political leaders.

So what do we actually know?

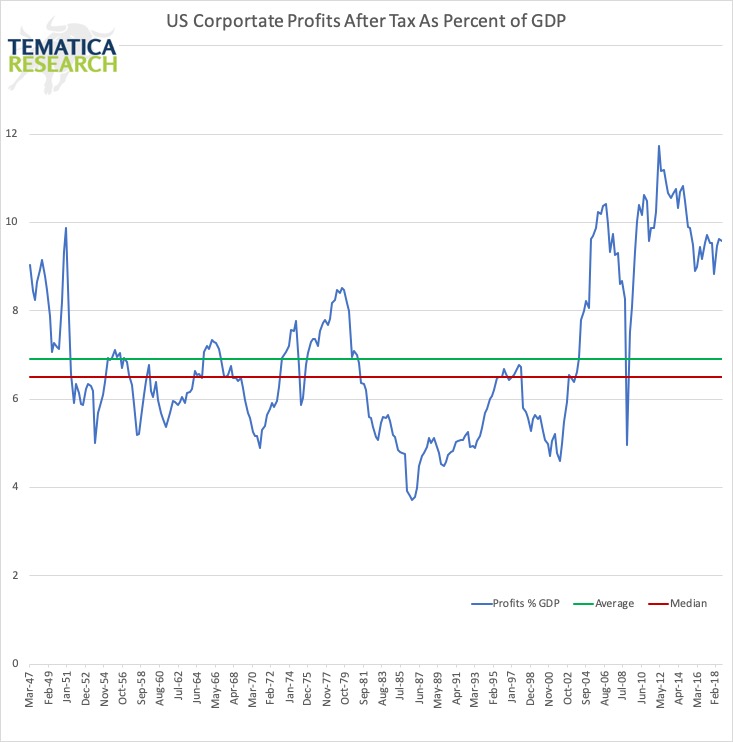

We know that US corporate profits after tax as a percent of GDP (say that five times fast) are at seriously elevated levels today, (nearly 40% above the 70+ year average) and have been since the end of the financial crisis. No wonder so many people

Corporate profits have never before in modern history been able to command such a high portion of GDP. This is unlikely to continue both because of competition, which tends to push those numbers down and public-policy. If the corporate sector is going to command a bigger piece of GDP, that means either households or the government is going to have to settle for a smaller portion.

It isn’t just the corporate sector that has taken a bigger piece of the GDP pie. Federal government spending to GDP reached an all-time high of 25% in the aftermath of the financial crisis and has remained well above historical norms since then.

Given the level of dissatisfaction we discussed earlier concerning

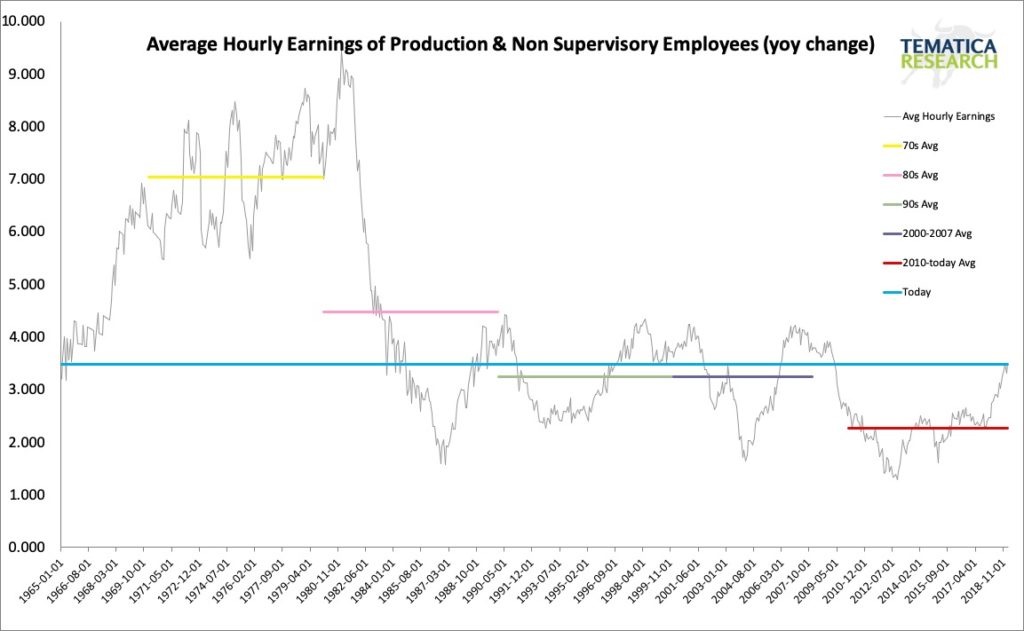

That leaves the households with a smaller portion of the economic pie – evidence of which we can see in all the talk around how wage growth remains well below historical norms.

Reversion to the Mean

Given the current political climate, it is unlikely that government spending as a percent of GDP is going to decline in any material way, which leaves the battle between the corporate and household sector. Again, given the current political climate (hello congresswoman AOC) it is unlikely that the corporate sector is going to be able to maintain its current outsized share of GDP – the headlines abound with forces that are working to reduce corporate profit margins and as we’ve mentioned earlier, global earnings are being revised downward significantly. If the corporate sector’s portion of GDP falls to just its long-term average (recall today it is 40% above and has been above that average for about a decade), it would mean a significant decline in earnings.

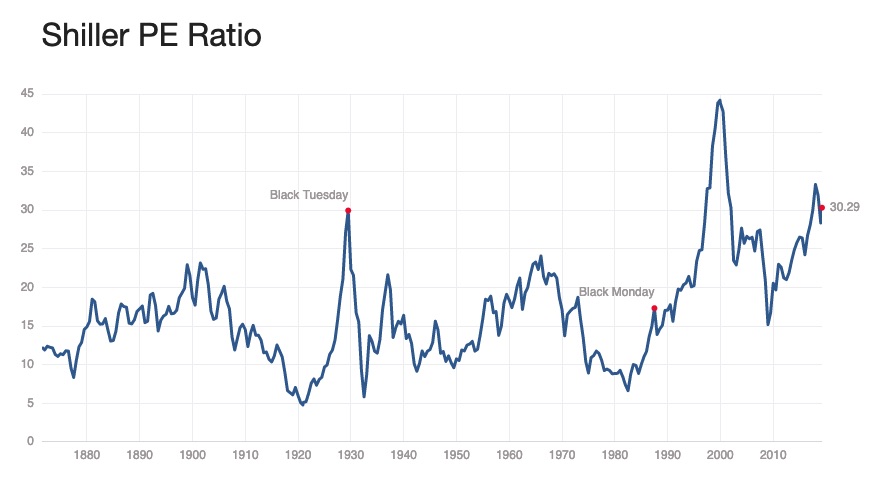

The prices investors are willing to pay for those earnings are also well above historical norms.

Today the Cyclically Adjusted PE Ratio (CAPE) is 82% above the long-term mean and 93% above the long-term median. What is the likelihood that this premium pricing will continue indefinitely? My bets are it won’t.

The bottom line is that the level of both corporate profits and what investors are willing to pay for those profits are well outside historical norms. If just one of those factors moves towards their longer-term average, we will see a decline in prices. If both adjust towards historical norms, the fall will be quite profound