Once Again the Fed Overestimates the Strength of the US Economy

Looking at the moves in the stock market, one would likely think all is right with the world and the US economy is back on track after bobbing and weaving around 2 percent GDP for much of the last several years. That is until we got the most recent reading on the health of the economy.

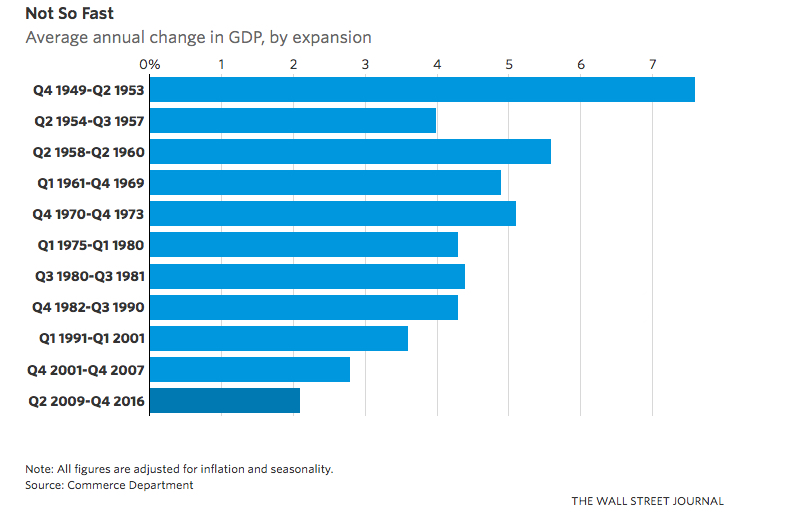

Friday’s estimate for fourth quarter 2016 GDP came in below expectations at 1.9 percent quarter-over-quarter, seasonally adjusted, versus the consensus expectations for 2.2 percent and the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate for 2.8 percent. The Fed’s consistently excessive expectations never cease to impress. To put 2016 in context, going all the way back to 1950, only four other years were as weak and they were all recessionary (1954, 1958, 2008, 2009).

This reading was a material decline from the 3.5 percent posted in Q3, but then that was primarily driven by an increase in inventories and exports. The net export contribution in Q3 was the largest since late 2013 was due in large part, and we are seriously not making this up, to soybean exports to South America where the weather decimated their soybean crop, adding a full 0.9 percent to the Q3 GDP growth. Exports in Q4 dropped -4.3 percent with goods declining -6.9 percent, revealing the headwind presented by a strong and strengthening dollar as net exports overall subtracted 1.7 percent from the fourth quarter’s growth. We’ve heard comments from a growing number of companies about the impact of the dollar and foreign currency translation in the current earnings season, but to put it in context, Q4 was the largest trade-related drag on overall growth since Q2 2010.

The U.S. economy decelerated in the final three months of 2016, returning to a lackluster growth rate that President Donald Trump has set out to double in the face of challenging long-term trends.

We are seeing some recovery in fixed investment, with fixed investment in mining, shafts and well structures contributing to GDP for the first time since Q4 2014, thanks to rising oil prices. While this contribution was relatively small, the removal of the headwind of low oil prices in this sector had allowed it to start contributing to GDP. We remain cautious here as the number of rigs coming online is rising week after week (see today’s Monday Morning Kickoff for more), and we remain skeptical that the OPEC deal on production cuts will survive given all the, shall we call them, colorful relationships involved.

Real investment in industrial equipment is at an all-time high, totaling more than $200 billion in 2009 chained dollars and looks to be still rising. On the other hand, investment in manufacturing structures is slowing a bit, which isn’t shocking given that capacity utilization rates are at levels normally seen around a recession.

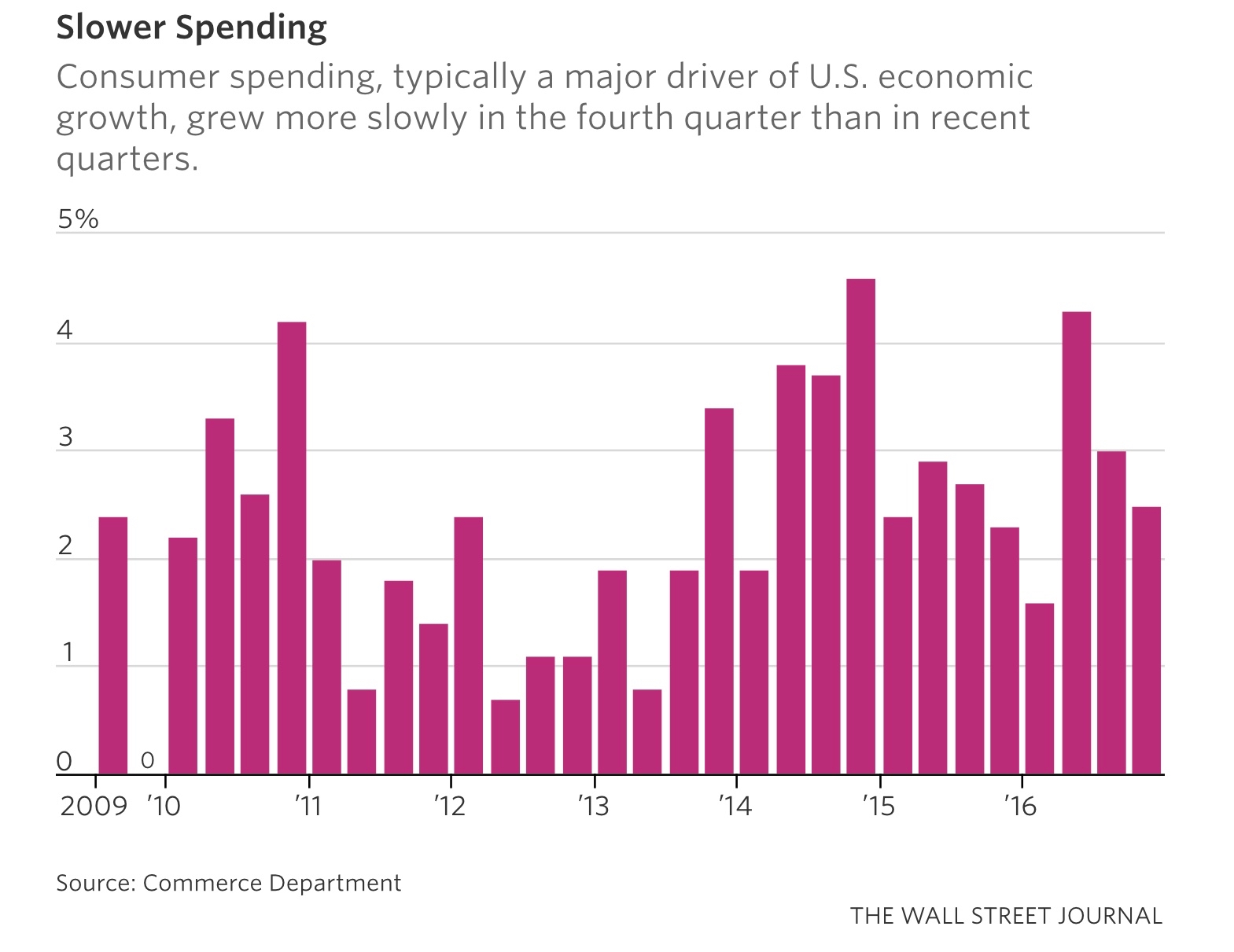

We have also now seen Consumer Spending decline over the past three consecutive quarters despite all the euphoric talk.

This brings full-year 2016 GDP growth to just 1.6 percent, putting the U.S. growth now in 2nd place within the G7 group with the U.K. delivering growth of 2 percent for the year. We are no longer the cleanest shirt in the laundry. This is the worst growth rate for the U.S. since 2011 and down from the 2.6 percent in 2015. America has now experienced a record eleven consecutive years without generating annual 3 percent GDP growth going all the way back to 1929. Is it any wonder there is a lot of frustration in the country?

Despite what we keep hearing from the Fed, this is not an economy that is accelerating. While over 80 percent of the survey data has come in above expectations, giving investors a sense of security, the actual hard data, rather than the more sentiment-oriented survey data, has seen over 50 percent come in below expectations.

With the recovery in oil prices and inventories back on the rise, two major headwinds have been removed, but the biggest and potentially most lethal remains – a rising dollar. The Fed still appears to be confident that it will raise rates three times this year which increases the dollars’ relative strength. Any trade barriers that result in fewer imports into the US, such as a 20 percent tax on fruits and vegetables from Mexico, would also serve to strengthen the dollar; the less we buy from the rest of the world, the fewer dollars are outside the country. That scarcity bids up the price of the dollar, particularly given the effectively massive short position in the dollar due to the over $10 trillion in dollar-denominated emerging market debt.

Mr. Trump has argued the U.S. can achieve stronger growth by overhauling the tax code, boosting infrastructure spending, rolling back federal regulations and cutting new trade deals that narrow the foreign-trade deficit.

The two big hopes that Wall Street has been relying on to boost the economy have been President Trump’s infrastructure plan and his tax cuts. This past week we saw signs that our concerns over when these would actually be enacted are warranted. Last week senior congressional aides revealed that the spring of 2018 is a more likely target for passage of tax reform legislation. According to Reuters, as the days passed at the annual policy retreat for Republicans last week in Philadelphia, leaders were also discussing that it could take until the end of 2017 or even later to pass fiscal spending legislation. Trump has taken office with the lowest approval rating in modern history and the level of controversy surrounding him isn’t declining, which will likely make passage of legislation he wants more challenging.

Putting it all together, despite the headlines over more sentiment-oriented reports, the economy does not look to be accelerating and the expectations around the timing of Trump’s infrastructure spend and tax reform plans are likely overly enthusiastic. Even the Wall Street Journal’s survey of over sixty economists projects GDP growth of 2.2 percent in the first quarter of 2017 and 2.4 percent in the second. We will continue to monitor the data to see how likely that consensus view becomes in the coming weeks. We believe the market is also incorrectly discounting the potential negative impact of a strengthening dollar and the degree to which this strengthening may occur.