Reaganomics v Trumponomics

The market has been giddy as all get out over the fiscal policies that it expects the Trump administration will push through in a relatively short period. We’ve discussed at length how the timeliness of legislation is likely to be less timely than the market is hoping for, so we’ll leave that alone for now. Instead, let’s just look at the potential impact of these moves, taking into account the impact of similar legislation in the past.

The popular refrain we keep hearing bandied about is a reference to the post-Carter economic boom of the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan. Team Tematica would love nothing more than to get back to that type of rip-roaring growth — not to be self-serving, but such an environment makes the job of an investment professional a heck of a lot less stressful when everything is going up!

Here’s the thing, there are more than a few material differences in the state of the nation and global economy that no mere mortal inhabitant of the White House could resolve in a matter of months or years. President Trump is indeed a mortal… granted an unusually orange one, but a mortal nonetheless. Sorry, that was too easy of a shot not to take, but let’s look at some of those differences…

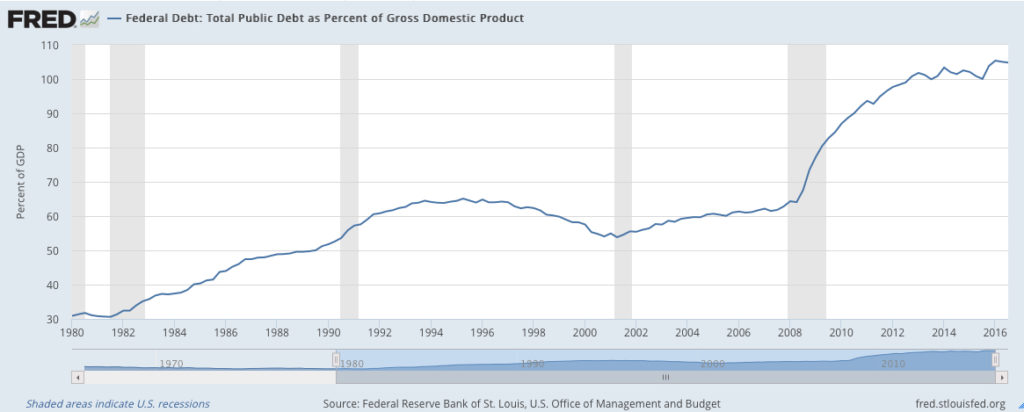

First, when Reagan took office, the total debt to GDP of the United States was just over 30 percent. Can you imagine? The headlines back then were also all about getting debt spending under control that the nation needed to work towards a balanced budget. When President George W. Bush took office the debt to GDP ratio was 57 percent. Today debt to GDP ratio is around 105 percent, 75 percent higher than when Reagan began, and around the levels at which warnings bells were going off concerning Greece a few years ago.

Many studies, most famously the one by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff entitled This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, have shown that as sovereign debt levels get above a threshold level, growth becomes increasingly hampered.

In other words, Reagan had a lot more wiggle room for fiscal stimulus.

We can see the impact of this debt burden in the fiscal spending multiplier. According to an analysis by Lacy Hunt, Ph.D. of Hoisington Management, from 1952 to 1999 $1.70 of government debt spending generated an additional $1 of GDP. From 2000 to 2015, each additional $3.30 of government debt spending generated an additional $1 of GDP. By 2015, it took $5 of government debt spending to generate $1 of GDP. Ah yes, the law of diminishing marginal returns we heard too much about in economics classes.

Speaking of fiscal stimulus, the markets are ecstatic over expected tax cuts both at the personal and corporate level. Back when Reagan took office, the top marginal income tax rate was 70 percent, which was cut during his two terms to 28 percent. Today the top marginal tax rate is 39.6 percent, giving Trump a lot less room for reductions.

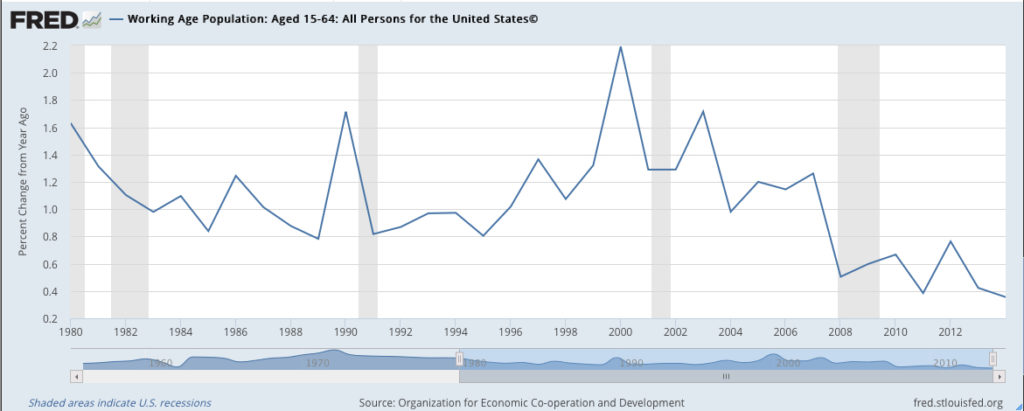

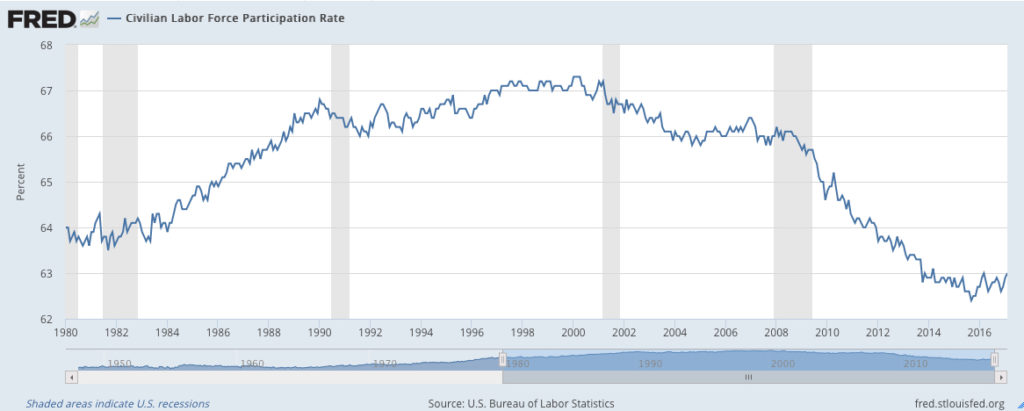

The workforce also looked a lot different under Reagan than it does today, as is reflected in our Aging of the Population investing theme. During Reagan’s term the working age population growing much faster than it is today.

The participation rate was also rising significantly and was at a materially higher rate than today. Today the United States has both the oldest population and the weakest population growth in its history. In 2016 population growth was 0.7 percent, which is the lowest since the 1935-1936 period with the fertility rate for women aged 15-44 tied for the lowest on record in 2013. For a bunch that looks heavily at thematic tailwinds, that is a major demographic headwind to growth.

With a lot more room to drop the top marginal tax rate and a much faster-growing workforce, Reagan was able to get a lot more bang for his buck. Today the current household formation rate is a painful 0.7 percent versus the average from 1960 to today of 1.6 percent.

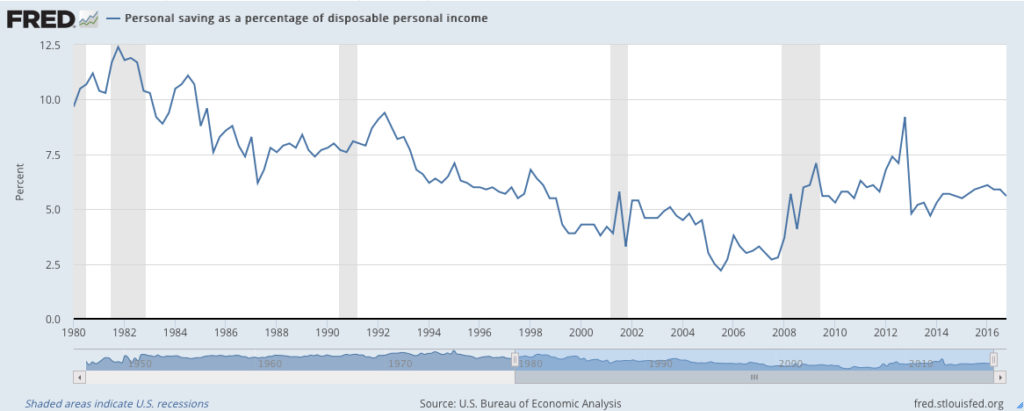

Back when Reagan took office, the savings rate was around 10 percent, whereas today it is about 5.4 percent. From 1900 to the present, the average savings rate has been much higher, at 8.5 percent, which means we are likely in the later stage of the expansion when pent-up demand has been exhausted with savings for many negative when we look at savings rate by income/wealth levels. With many living paycheck-to-paycheck, as we regularly discuss in our Cash Strapped Consumer theme, the economy is increasingly vulnerable to shocks. This low savings rate also has repercussions inside our Aging of the Population investing theme, especially since roughly half of all baby boomers have little to no retirement savings.

Disposable personal income per capital growth over the past ten years has been less than 50 percent of the norm since World War II. Higher income allowed for a higher savings rate that also generated higher returns which translated into greater spending capacity, as interest rates were much higher.

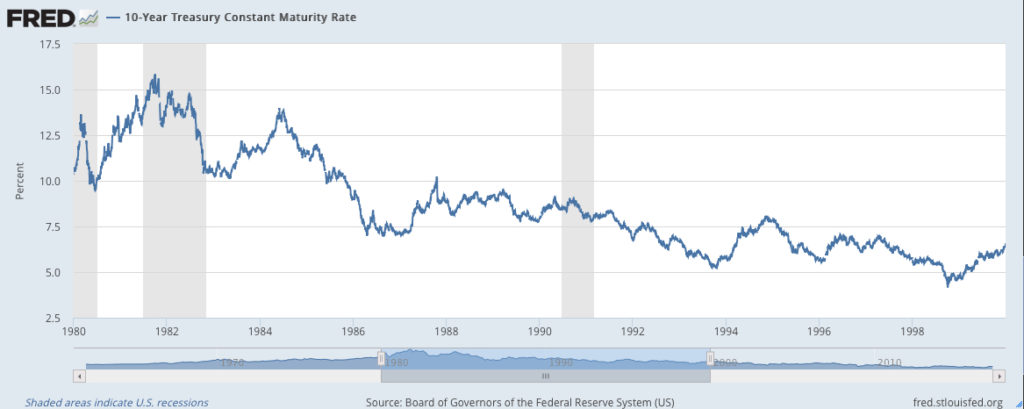

During Reagan’s term, the 10-year Treasury rate dropped from a peak of nearly 16 percent to a low of 7 percent – talk about stimulative! Today interest rates remain near record lows with the Fed in the midst of a rate hike cycle. On top of that, we are seeing the beginnings of tightening loan standards and declining demand for credit, which is part of our Economic Acceleration/Deceleration theme.

From the Federal Reserve’s January 2017 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, the most recent data available:

Regarding loans to businesses, the January survey results indicated that over the fourth quarter of 2016, on balance, banks left their standards on commercial and industrial (C&I) loans basically unchanged while tightening standards on commercial real estate (CRE) loans. Furthermore, banks reported that demand for C&I loans from large and middle-market firms, alongside small firms, was little changed, on balance, while a moderate net fraction of banks reported that inquiries for C&I lines of credit had increased. Regarding the demand for CRE loans, a modest net fraction of banks reported weaker demand for construction and land development loans and loans secured by multifamily residential properties, while demand for loans secured by nonfarm nonresidential properties reportedly remained basically unchanged on net.

Regarding loans to households, banks reported that standards on all categories of residential real estate (RRE) mortgage loans were little changed on balance. Banks also reported that demand for most types of home-purchase loans weakened over the fourth quarter on net. In addition, banks indicated mixed changes in standards and demand for consumer loans over the fourth quarter on balance.

Most domestic banks that reportedly tightened either standards or terms on C&I loans over the past three months cited as an important reason a less favorable or more uncertain economic outlook. Significant fractions of such respondents also cited deterioration in their current or expected capital positions; worsening of industry-specific problems; reduced tolerance for risk; decreased liquidity in the secondary market for these loans; deterioration in their current or expected liquidity positions; and increased concerns about the effects of legislative changes, supervisory actions, or changes in accounting standards.

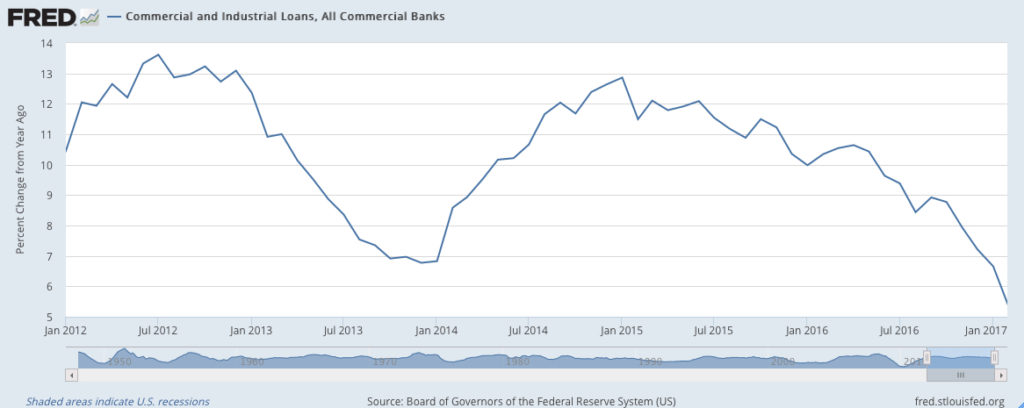

This is typical of the later stages of the business cycle and regardless of what the Trump administration does, is a headwind to growth. In addition to the survey, we can see that since peaking around January 2015, the loan growth has been declining significantly, again one of the headwinds of our Economic Acceleration/Deceleration theme.

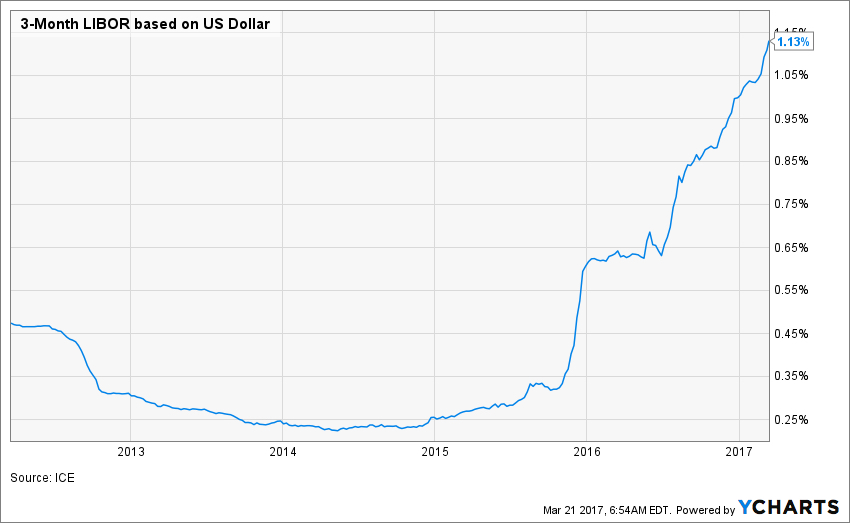

We can also see rising rates reflected in LIBOR rates, to which many mortgages are tied, which helps explain the declining demand for mortgages.

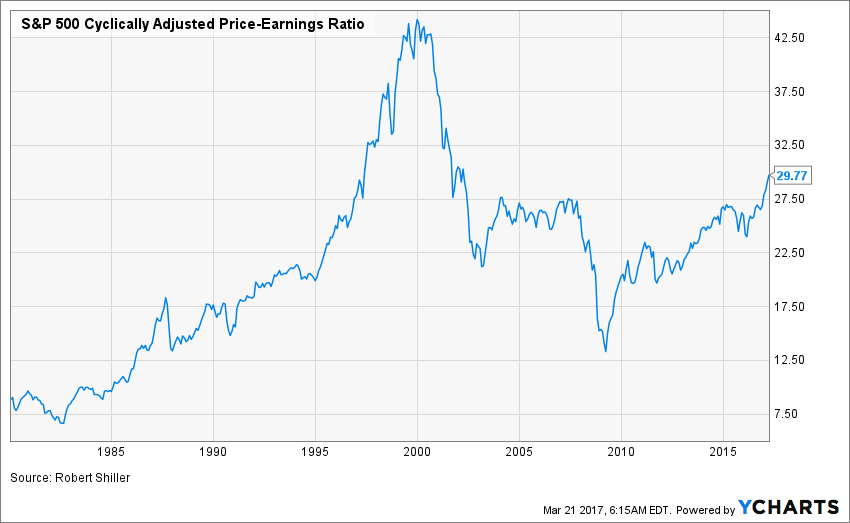

Finally, for investors, there was a lot more room for stock prices to go up in the 1980s compared to today’s market.

When Reagan took office, the Shiller Cyclically Adjusted Price-Earnings ratio was under 9, dropping to less than seven as Paul Volker hiked interest rates dramatically to crush inflation. By the end of his term, it had risen to just over 17 then continued to increase during the 1990s, peaking in 1999 at over 43. Today this measure stands just shy of 30, nearly four times what it was shortly after Reagan took office.

To put it all together, Reagan benefited from a labor pool that was growing much more rapidly than today, a higher starting point for the marginal tax rate, the stimulative effects of falling interest rates and a higher starting savings rate. During Reagan’s term investors benefited from much lower starting stock valuations.

The bottom line is that while many of the policies suggested by the Trump administration would likely have a stimulative effect, they must be assessed within the context of today’s economic reality.